Mark Neveldine and Brian Taylor present us with a cinematic experience remarkably akin to a caffeine, drugs, sugar and alcohol binge as the audience is tumbled into a desensitizing, hyper-kinetic and over-stimulating world designed to force only the most echoing thumps from the heart and every drop of sweaty suspense from the pore. We enter a futuristic, dystopian world where technology has reached the pinnacle of its potential and perhaps inescapably, humanity has regressed and de-evolved mentally and emotionally so that everyone is shiny, superficial and shallow; a flawless cold demeanor with a selfish heart; a world where the id is King.

This not-far-off world takes degenerative aspects of current society and reinforces them pushing them to the extremity, the nth degree. Set in the not-too-distant future, the society of Gamer is one of violence and depraved sexuality but all of this depravity occurs not in reality, but can be experienced voyeuristically or vicariously through playing characters thanks to the games of rich boy entrepreneur Ken Castle (suitably slimy Michael C. Hall). Gamer sets up two un-real, artificial worlds; that of ‘Society’ and that of ‘Slayers‘; both of which are eaten up by capitalist, consumer ridden society who appear to sacrifice moral values and human interest for cheap and instant thrills. The society is naturally insatiable and constantly baying for more blood and more sex.

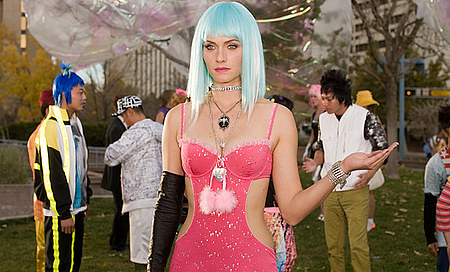

Society enables people to pay either to control or be controlled. In this fantasy world there is dehumanization, humiliation, pain, rape, promiscuity, alcoholism and drug use. The glittery, showy world of slick surfaces is as insubstantial as cotton candy, and yet rotten to the core. ‘Society’ is gauche, garish and almost offensively kaleidoscopic and multifaceted as a diamond, reminiscent of the explosion of a rainbow. Yet the overwhelming acidic aesthetics, slickly polished environments and promiscuous Lolita fashions are cold, uncomfortable and wholly devoid. The frequent nudity and forced sexual scenes feel incredibly awkward because we are witnessing the complicit commoditization of rape and of the body as a money-making vehicle exploited for its capacity to fulfill the twisted pleasures of others. As Rick Rape ( a jittery Milo Ventimiglia) forces himself upon the frozen Angie (a beautifully cold Amber Valletta), sexuality transforms into something clinical, abnormal and abhorrent as obese men sit in dark, dank bedrooms trying to arouse other men by portraying sexualized female characters who spout obvious innuendos whilst dressed as pussy cat dolls.

If ‘Society’ works on the individuals desire to control sexuality, then ‘Slayers’ works on the individuals desire to control violence. Real prisoners must fight for their freedom whereby if they survive 30 missions they are exempted from the death penalty. This world is gritty, bare and stripped to the bare minimum; a masculine pandemonium of blood, survival and rage. Gerard Butler is Kable, the only man to come in reaching distance of freedom who is in turn played by Simon (Logan Lerman) who portrays perfectly the adolescents desire to receive an influx of never-ending stimulation all the while yawning and sneering in its face.

The film explores the dangers of living in a world where humanity is completely independent and fragmented; where people can control and manipulate others. The totalitarian reigns of Hitler, Stalin and Napoleon may be over but in this world the internet reigns supreme. Parodying fads such as Facebook, Second Life, Big Brother, Call of Duty and the abundance of pornography that has infiltrated mainstream society, ‘Gamer’ is disconcerting purely because it contains more than a grain of truth, cashing in on three key social fads; sex, violence and video games. This satirical portrayal gets us to sit up and take notice of the direction in which our world is going - a world where the pleasure principle rules. The only hypocrisy of the film is that whilst on the one hand it condemns violence and sexuality, it makes gratuitous use of it; an uneasy but very watchable film which explores societies sub-cultures and blends with dark science-fiction.